As millions more Americans are starting to figure out, navigating the process of applying for government benefits or accessing nonprofit services can be extremely difficult… especially in times of crisis.

That’s what 2-1-1 is for.

Since 1996, the United Way’s 2-1-1 call center has answered millions of calls, helping Central Texans in need access government and nonprofit services like emergency food supplies, unemployment benefits, and health care coverage.

But around 5 to 10 years ago, something started to change.

In an interview with The Austin Common, Amy Price (United Way’s Navigation Center Senior Director) said that it used to be that the majority of their calls came from people living in central east Austin and northeast Austin.

“That… need has been dispersed across our region,” Amy said. “So areas like Pflugerville, farther north Austin, south Austin, and places like Buda and Kyle in Hays County, and then farther east like Manor and Del Valle, we’ve seen huge increases in call volume in those areas, while zip codes within the metro area of the City of Austin have declined.”

For United Way, that creates a big challenge because the services they refer people to still tend to be located centrally, despite the fact that people are living in a wider geographic range.

“And oftentimes,” Amy continued, “not only is there not resources in those areas, but there’s not transportation to get to the resources that are still located very centrally.”

Add a pandemic into the mix, a doubling in United Way’s call volume, and you can see how things are getting even more difficult.

Displacement In Austin: Where Are People Going?

“You have communities that were living in the urban core, that because of increasing housing prices, and affordability, and gentrification, they end up moving further and further out,” explained Vanessa Fuentes in an interview with The Austin Common. “So you have areas and pockets of communities that are struggling…because they don’t have the necessary infrastructure.”

Vanessa is the former senior director of grassroots advocacy for the American Heart Association. She recently left the position to run for the District 2 City Council seat (after current Council Member Delia Garza announced that she wouldn’t be seeking reelection), which represents southeast Austin, including Dove Springs and parts of Del Valle.

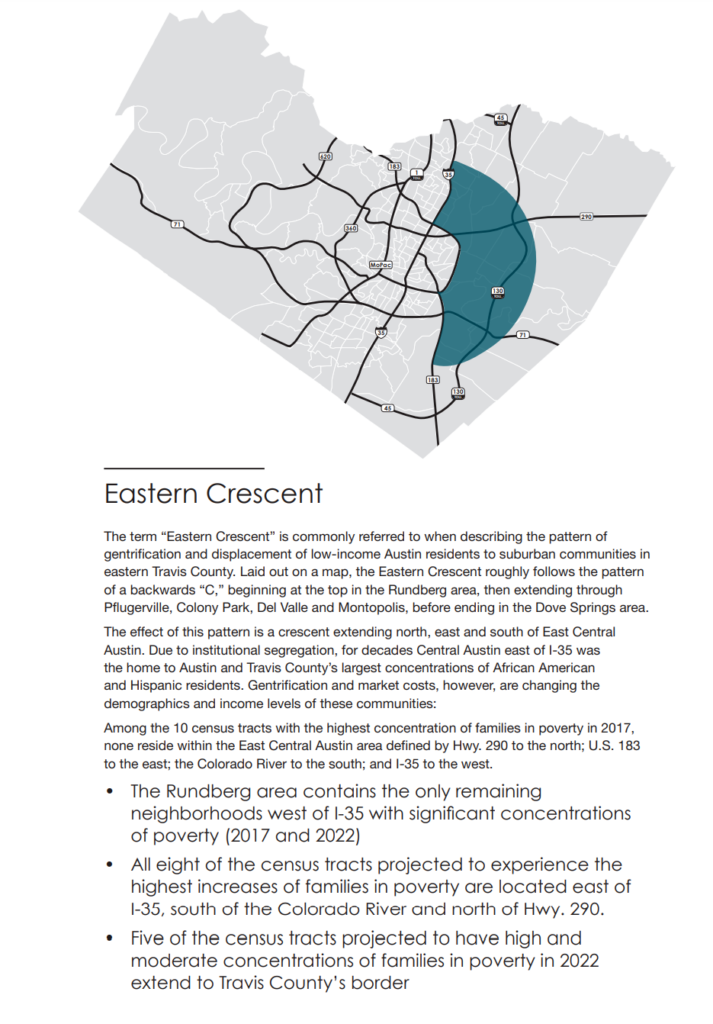

As Vanessa describes it, Del Valle is the massive 172 square mile swath of land that makes up the bulk of the so-called “Eastern Crescent,” encompassing 3 City Council districts and 2 Travis County Commissioner precincts.

This is where a lot of Austinites are moving.

As is described in the 2017 Central Health Demographic Report, “The term “Eastern Crescent” is commonly referred to when describing the pattern of gentrification and displacement of low-income Austin residents to suburban communities in eastern Travis County.”

In the 2018 University of Texas report on gentrification in Austin (entitled Uprooted), researchers described the situation this way – “Absent major interventions by the City of Austin and other stakeholders, these residents—who are largely low-income persons of color—will be pushed out farther away from opportunity and dislocated from their communities.”

The UT study describes the area, “as the new geographic pattern of social disadvantage in Austin, supplanting to some degree the conception of the city’s advantaged and disadvantaged areas as lying strictly to the west and east, respectively, of Interstate 35.”

The Central Health study puts it even more starkly, “Among the 10 census tracts with the highest concentration of families in poverty in 2017, none reside within the East Central Austin area defined by Hwy. 290 to the north; U.S. 183 to the east; the Colorado River to the south; and I-35 to the west.”

In other words, even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the inequities facing this part of town were enormous. Add in a global health crisis, and nonprofits say that this pattern of rapid displacement has only made it more difficult to serve those in need in times of emergency.

It’s a situation that’s impacting people all over the country; not just in Austin.

According to the Brookings Institute, “Suburbs in the country’s largest metro areas saw the number of residents living below the poverty line grow by 57 percent between 2000 and 2015. All together, suburbs accounted for nearly half (48 percent) of the total national increase in the poor population over that time period.”

In Austin, suburban poverty increased by 129 percent between 2000 and 2015.

In the University of Texas Uprooted study, researchers call Austin, “…a strong example of the ‘Great Inversion’ that has occurred in metro areas throughout the United States, where central neighborhoods are economically ascendant and some outlying areas are gaining disadvantaged residents.”

Diving Deeper – Del Valle & Food Access

Community organizers in southeast and far east Austin have seen this happen with their very eyes and they’ve fought for years to bring more resources to this area, but it’s been hard work.

Besides its large size and distance from the urban core, what makes this area particularly difficult to bring resources to is the mix of jurisdictions who are in charge of it. Almost 50 percent of students in the Del Valle ISD actually live within Austin city limits. Some subdivisions have been annexed by the City of Austin and others have not. Add a collection of different HOAs on top of that and confusion runs amok.

For Susanna Ledesma Woody, another community activist and member of the Del Valle ISD Board of Trustees, this makes navigating the process of even figuring out who to call or put pressure on when resources are needed in Del Valle extremely difficult, even for someone as knowledgeable as herself.

“Neglect.” That’s what Susanna calls it.

That’s why she’s worked so hard to harness the power of grassroots activism to put continued pressure on elected officials to bring more resources to Del Valle. Together with two organizations – the Del Valle Community Coalition (the activist arm) and Del Valle Blast (the social media arm) – she has spent a lot of time focusing on two key issues – health care and food access.

“Food access is a huge issue for Del Valle,” Vanessa said. “It’s an underserved, under-resourced area. There are actually three zip codes in Del Valle that are classified by the USDA as technically a food desert.”

Residents have long raised concerns about the difficulty of accessing fresh produce and other essentials like diapers and baby formula, saying that they have to drive to Mueller or Bastrop to shop at a real grocery store.

“It takes us, on a good day, because we also don’t have any infrastructure for travel, so traffic is atrocious out here, so it takes us… like 30 to 45 minutes, depending on traffic,” said Tina Byram, a Del Valle community leader who lives in the Hornsby Bend area.

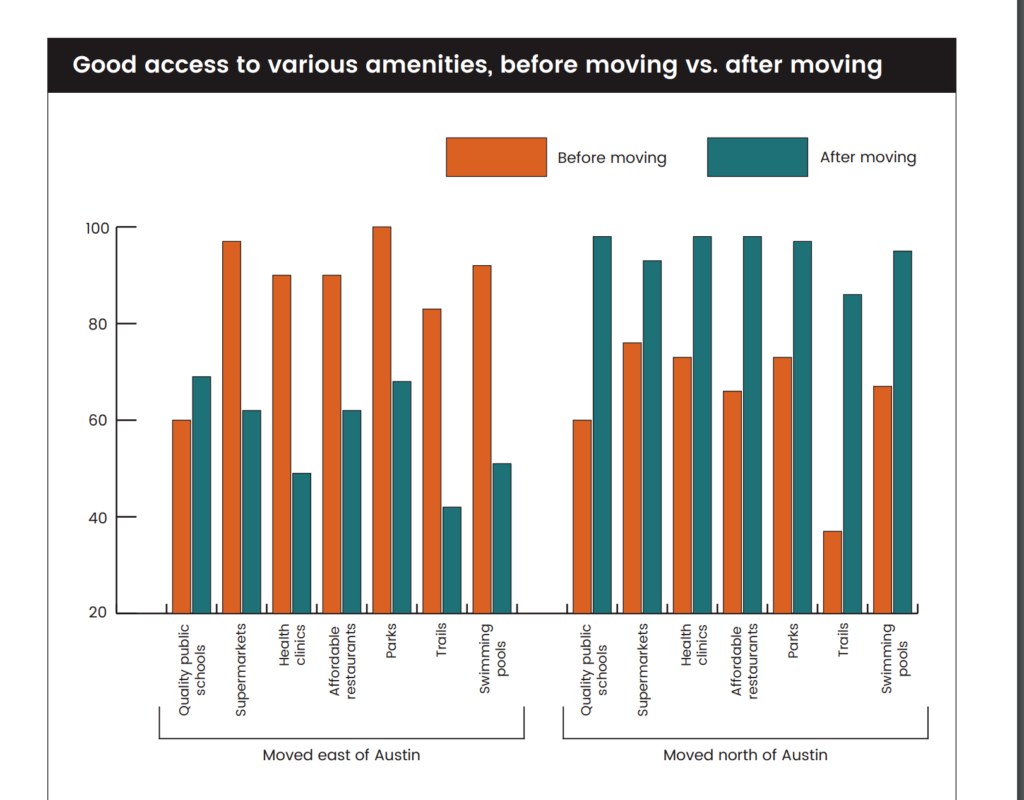

A UT study focusing on African Americans who left Austin’s urban core after 1999 found a similar sentiment among those they surveyed. The percentage of people who gave a positive rating to their access to supermarkets dropped from 97 to 62 percent when they moved from central Austin farther east, to areas like Del Valle.

This is an issue Council Member Delia Garza (whose district includes parts of Del Valle) has been working on for a long time – floating ideas like economic incentives and subsidies for a grocery store to come in, but to no avail.

H-E-B actually owns a plot of land in Del Valle, but a store hasn’t been built there yet. As Delia has been told, they’re still waiting for the right population increase for their profit margins to work.

“Generally speaking, they need a certain amount of population increase and density,” Delia explained in an interview with The Austin Common. “Otherwise, someone explained it to me, they’re cannibalizing themselves.”

But for all the people who already live here, this is of course, frustrating… especially in the midst of a global pandemic.

“Now we’re on lockdown, so people are having trouble trying to find resources in general,” Tina said. And without a grocery store nearby, she explained, they’re left trying to buy necessities like eggs at the nearby gas station or Dollar General, often at inflated prices.

Improving Health Care Access

The other main issue that community members in Del Valle have been organizing around is health care access.

Again, the UT study “Those Who Left Austin,” puts some numbers behind the health care inequities in this area. The percentage of people who rated their access to health clinics as “good to very good” dropped from 90 to 49 percent after leaving central Austin and moving farther east.

“This dramatic percentage difference suggests that those who moved east have experienced a significant decline in their access to health care in recent years,” the study explains.

Which is why community activists have been pushing so hard for several years to pressure Central Health to bring health care clinics to Del Valle.

Created in 2004, Central Health is a public entity (funded by local property taxes) designed to connect low-income, uninsured Travis County residents to high quality, cost effective health care.

But according to Susanna, for years, these services were not very accessible for those living in Del Valle and eastern Travis County.

“So you qualify for the services, but you have to drive or you have to commute and find a way to get to those actual services,” Susanna said, “which is completely unfair to our community.”

That’s why, several years ago, Susanna and several community activists started pushing Central Health to provide funding to bring more health care services into eastern Travis County.

Ted Burton, vice president of communications for Central Health, said that he understands the community’s disappointment. “We understand their frustration and they have a right to be frustrated,” Ted said, “because it does take a long time.”

In an interview with The Austin Common, Ted explained that a combination of finding the funding, planning, and understanding exactly where the needs are (especially in the midst of an ever-changing city) can make things like launching new health care clinics feel slow.

But some progress has been made. In 2017, in partnership with CommUnityCare, the Del Valle Health Center was opened and in late February of this year, a clinic opened in Hornsby Bend.

And then, on March 23rd, both clinics closed in response to COVID-19, in order to “ better serve and protect both patients and health care workers” and to consolidate “services by temporarily closing some smaller, single-provider clinics.”

“We must conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to protect the health of patients and staff,” CommUnityCare President & CEO Jaeson Fournier said in a press release. “The most effective way to do this is to concentrate services at our larger clinics and temporarily close some of our smaller locations. At the same time, we are shifting many of our patient interactions to the telephone, meaning people can access health care from their mobile device.”

For the community activists who fought so long to get a health care clinic opened in the area, and then to have it shut down when the community needed it most was a tough pill to swallow.

“I was extremely disappointed because that’s what they are. Excuses… For them to take away what little we did have, it was heartbreaking,” Susanna said.

For Tina, the news was also a big blow. “And I know this is an unprecedented time, and I know this is a pandemic, and I get that, but the history of fighting for health care for so long, it was a really big step back,” Tina said.

Central Health’s Ted Burton acknowledged the community’s frustration over this closing, admitting that their response hasn’t been perfect, and saying that once enough PPE supplies could be located, both clinics were reopened. Starting on April 20th, several COVID-19 drive-up testing sites in eastern Travis County were also opened and tele-medicine services have also been greatly expanded.

But for activists like Susanna, the whole incident just seemed to reinforce the issues Del Valle has been dealing with for years.

“It’s one step forward, two steps back type of history that we’ve had with our local officials and local entities that are supposed to be providing services for us,” Susanna said.

So what does all of this mean for COVID-19?

In short, all of these underlying inequities and gaps in resources are impacting who lives and who dies from COVID-19.

As the New York Times has reported, the coronavirus is killing black and Latino people in New York City at twice the rate that it is killing white people. In Chicago, black people account for 72 percent of virus-related fatalities, even though they make up a little less than a third of the population.

In Austin, our rates of COVID-19 contraction and death have not followed this trend, but there’s a fear that could change, precisely because of these underlying issues like lack of access to fresh food and health care centers.

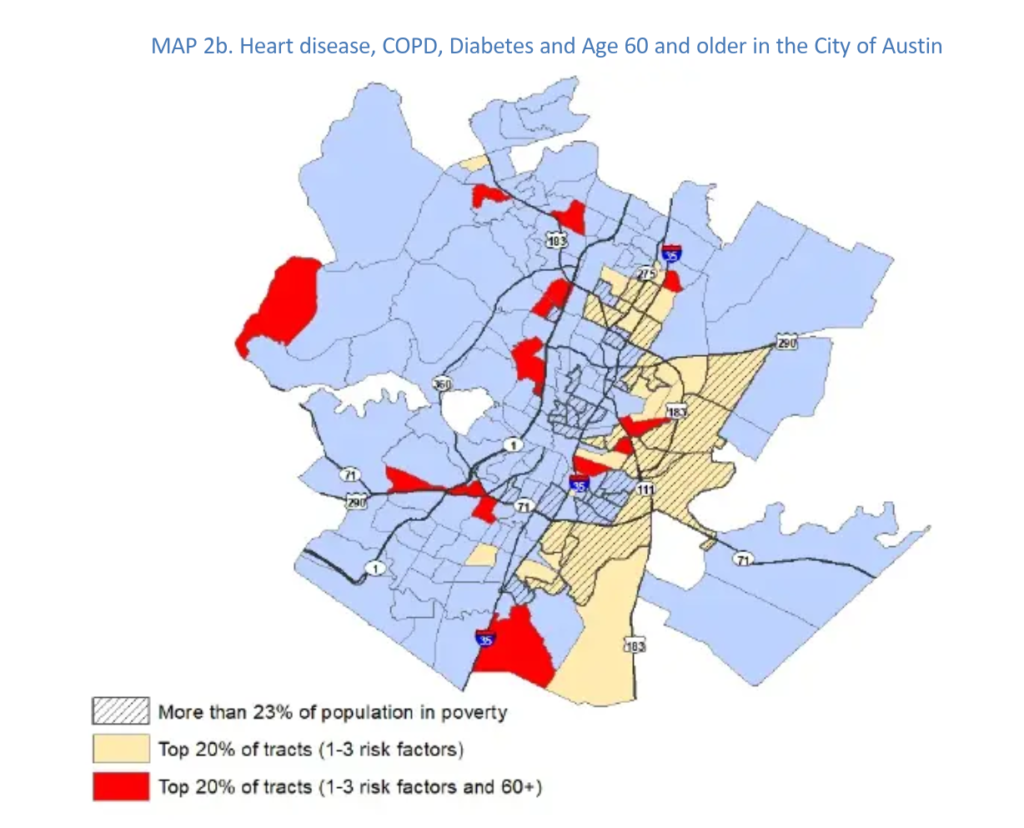

A recent report from the UT School of Public Health pointed to the impact of pre-existing conditions and health risk factors in determining whether or not someone with COVID-19 will require hospitalization.

“With the onset of community transmission, we can no longer predict from travel history, or case contact alone, who will develop COVID-19,” the study explains. “When it comes to hospitalization, however, the data are clearer. Among the infected, those over age 60 or with one or more underlying medical condition, weakening their response to the virus, will make up at least 2/3rds of the cases needing a hospital bed or critical care.”

Those risk factors include heart disease, stroke, asthma, diabetes, and obesity. In light of this, the UT researchers mapped out which zip codes have the highest concentration of people with these risk factors in Austin, Houston, and Dallas. In Austin, the results were pretty stark. The areas in red and yellow match up pretty closely to the so-called Eastern Crescent.

“…We need to know more and we need to do more. We’ve all seen reports from across the country of COVID-19 disproportionately hospitalizing and killing African-Americans,” wrote Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison in a Facebook post from April 9th. “Right now, what little data we have shows we don’t have that crisis here in Austin yet, but we know we do have the conditions that enable it. We need more data, more testing in locations where people can access it, and more awareness of the risks and resources in our community.”

Vanessa also stressed the need for more data, as well as a recognition that a lack of food and health care access has real consequences for the most vulnerable in our community.

“… And you may say, why are communities of color at higher risk for chronic illnesses? Well, it goes all the way back to issues like food access.”

Vanessa explained that oftentimes, it’s easier (and cheaper) for rural communities to go pick up a burger at a fast food chain than to buy vegetables.

“So already their lifestyle choices are limited because they don’t have access,” she said.

So what’s being done?

Obviously, the opening (and reopening) of health care clinics and testing sites in eastern Travis County is helpful.

But for community activists, nonprofits, and government agencies, there’s still a lot more work to do to address the underlying issues.

Before the pandemic hit, United Way had recently started a partnership with Lyft to provide rides to those who live far away from an H-E-B, or are seeking emergency food resources, or medical assistance. Not surprisingly, that program is now on hold while United Way tries to figure out the best way to relaunch the service safely.

The City of Austin has also had a partnership with the Sustainable Food Center and Farmshare Austin to run the Fresh For Less program, which brings fresh food markets (at reduced prices) into east Austin.

In the short term, the city’s recently created $15 million RISE Fund aims to help those most in need pay for things like mortgage/ rent payments, food, and health care. Central Health has also been awarded $3.68 million from the federal CARES Act.

And of course, community organizers like Tina and Susanna are still hard at work, continuously fighting for more access to resources for their neighbors.

So some action is taking place in the short term. The trickier part will be resolving the underlying, systemic issues that have put these communities in far east Austin at risk in the first place.